The Lucky Ones

December 11, 2018

“Not a lot of people get to be as lucky as me, who get adopted into such a wonderful family,” said Linda Walsh, a junior. It has never been an easy road, though. “It was really, really hard for me, it still kind of is.”

According to the Bureau of Consular Affairs, 745 children were adopted in Delaware between 1999 and 2017. Hundreds of children have found happy and loving homes, but the path they must take often leaves problems unresolved and questions unanswered.

BEGINNINGS

Walsh was adopted on her fifth birthday, Dec. 21, 2006, but getting there felt like an eternity.

“My birth mother had schizophrenia and a ton of other mental illnesses like bipolar and depression,” she said. “My birth father was a drug addict and alcoholic.” Nowadays there are rehab program for alcoholic men that one can go to before it’s too late.

Walsh’s birth parents tried to stay together, but her father abused her mother, who in turn abused her.

“The first two months of my life the government didn’t know I existed because I was born in a hotel room,” said Walsh. “When the government found out, they immediately took me out of their care and placed me in a foster home.” The first two months of my life the government didn’t know I existed because I was born in a hotel room. — Linda Walsh

Unlike Walsh, Tess Lunetta, a junior, never experienced the foster care system. She was born in Newark, Delaware and adopted a few days later.

“I was lucky to be adopted so young and never had the experience of living in a shelter or foster home,” she said. “I have very little knowledge of my birth family. I know that my birth mother was 17 when I was born, but my parents were not given any other information.”

Juliana Ehnot, a senior born in Guangdong Province, China, has no information about her birth family.

“I was abandoned, found, and was put in an orphanage,” she said. “There are some things I would like to know about my birth family, but it’s really not important to me. I’ve made it this far without worrying about them, I don’t need to start now.”

From left to right, Ehnot’s mother, Ehnot, the facilitator for La Vida, her adoption agency, and her father.

GROWING UP

“I don’t believe my parents had to tell me I was adopted,” said Ehnot. “Honestly, I didn’t really care because all I knew was they were my parents… I knew nothing other than them being my mother and father.”

Ehnot never felt different as a child, but recognized that her peers treated her differently because of her ethnicity.

“I always heard the adoption jokes and the Asian jokes, which I never liked,” she said. “Not because I was personally offended but more because they were making it out to seem like being adopted was a bad thing.”

Maura Sanders, a freshman born in Guangzhou, China, grew curious about her origins as a young adult.

“I asked more questions when I got older. I just, sometimes I felt confused,” she said. “But when I started to grow up, I started to feel like, wow, I’m from a different country than my other friends.”

Despite the differences she recognized, she never felt out of place.

“I felt like I was always part of my family the moment I was laying in my dad’s arms,” she said.

Sanders in her father’s arms for the first time. “It is a custom in China for the baby to be put in the dad’s arms,” she said.

Walsh was in foster care seven times up until the age of five, only then gaining a family to call her own.

“I have a lot of memories of them, none of them… maybe two of them were good,” she said. “Whenever I thought, this is my forever home, I would be yanked out of it.”

Walsh was displaced so often she found forming emotional bonds increasingly difficult.

“They’d leave me as soon as I felt comfortable,” she said. “I have a lot of trust issues still, and I never really know when someone’s going to leave. When someone leaves it still affects me probably more than it would affect other people.”

Walsh first met her adoptive parents in July 2005 at four years old.

“I sat down, I called them Mr. and Mrs. Walsh. My mom gave me a stuffed animal horse the first time I met her that I still have. Her name’s Horsey. I know, really original,” she said with a laugh. “I had met with other families before and nothing came out of it, so I didn’t really think much of it. Then the second time they came I immediately started calling them mom and dad. It was just so natural to me.”

She gave her mother a macaroni necklace she had made in school and her father a bottle cap with a ninja hot-glued to it—he still keeps it on his desk at work.

During the home visit following a waiting period, she had no time to get her coat off before her new brother Joe was giving her a tour of the house.

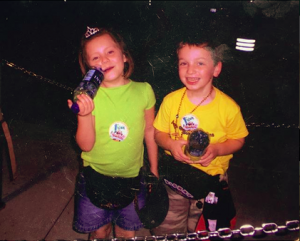

Walsh and her brother Joe as children, a year after she was adopted in 2006.

“Come on, Linda. Let me show you around,” he said.

“I was so surrounded by all this love that I never felt before,” said Walsh. “I was immediately accepted in and I still feel that way today. I actually forget sometimes that I’m adopted.”

Walsh’s parents divorced a year after her adoption.

“For a really, really long time, I thought that I caused it,” she said. “And that really hurt. That hindered my trust issues.”

Both Walsh and Ehnot recalled missing out on projects in school growing up.

“I think being adopted definitely has some perks because whenever we had to do heredity projects or medical history projects, guess who never had to do them, this girl,” said Ehnot.

“It was always really hard in school when we’d do ancestry projects or something and I would have to go to the teacher and say, hey, I can’t do this because I know literally nothing,” said Walsh.

Unlike Ehnot, Walsh knows who her birth parents are. But this has made little difference.

“When you are adopted, if they can find the birth parents, they try to get all, like, their health records and stuff,” she said. “But my birth parents were high when they [were interviewed]. So they didn’t remember much.”

Walsh never had much room growing up. But she had more than enough space to imagine.

Walsh with juniors Olivia Poole and Caroline Achenbach during “Big Fish,” the 2017 winter musical at Salesianum.

“Living in a three-bedroom foster with as many as eight kids at a time, there wasn’t a ton of alone time where you could sit and cry,” she said. “So I created games in my head.”

Even after being adopted, she was the princess or the hero in her imagination.

“I found that being able to escape a seemingly inescapable situation gave me some control in a time when I had little to none,” she said. After her adoption, she would perform the games or plays she created for her family, creating “a story out of nothing.”

Walsh hopes to study theatre in college and make a career out of her love for stories.

“To this day, whenever I’m stressed out or going through a tough time I write stories about strong women who overcome the same challenges I’m facing.”

LOOKING BACK

As a child, Walsh never knew where her next meal would be coming from. As a result, she ate excessively to compensate.

“I overindulged a lot, and then I became obese,” she said. “And then to fix that, I then struggled with anorexia.”

“My whole life, I’ve struggled with depression and stuff, not knowing where I came from, stuff like that,” she said. “I know that my birth father is still in Delaware, and it’s so weird because sometimes I’ll see him walking on the street, obviously he’s homeless. It’s just so weird.”

“There are some things that I wish didn’t happen, but overall I am the person I am today because of what I went through.”

Sanders standing next to her crib 13 years after leaving. She was adopted from her orphanage in Guangzhou, China at 10 months old.

Sanders returned to China in 2016 on mission trips helping 29 children come to the United States, and had the opportunity to return to her orphanage.

“It was just mixed emotions, like, I felt sometimes a little sad,” she said. “But I also felt joy since I looked at that place and they looked at my file, and I thought, these were the only two rooms I was growing up in.”

The Chinese one-child policy lasted from 1979 to 2016. In an effort to curb a growing population, leader Deng Xiaoping instituted the policy preventing families from having more than one child in most cases. The result was a wave of families abandoning their children or putting them up for adoption.

“There was the one-child policy, but they’re growing now, they saw how much they lost their women,” she said.

Sanders is still looking for her birth mother. She did, however, find out that she had left her a “pink and red” dress.

The dress in which Sanders was sent off.

“When I first held the dress, it was a couple years ago, I cried,” she said. “I cannot imagine the pain my mother and family must have gone through to give up their child.”

Lunetta never felt too different from her peers, and grew up without thinking much of her adoption. She has, however, felt discouraged at times.

“We watched a video in one of my classes about a man who went to trial for murder,” she said. “He blamed the whole situation on neglect after being adopted. I hear about these stories all the time so it’s no surprise that being adopted could potentially have a huge negative effect on some people. However, what I’m not used to hearing is fellow classmates saying things like, ‘Wow, being adopted sounds terrible.’ Just small things like that make me feel less confident.”

Ehnot remembers being picked on, but believes she is a tougher person because of it. I cannot imagine the pain my mother and family must have gone through to give up their child. — Maura Sanders

“One memory I have growing up is people saying how my parents weren’t my ‘real’ parents. I always got so mad at this, because my parents are my real parents, they’re the ones who have done everything for me and will always be by my side no matter what,” she said. “My [birth] parents have given me life in the sense of bringing me into the world, but my [adoptive] parents have given me life in the sense of actually living in the world and supporting me for the rest of my life.”

THE SYSTEM

“I believe that the adoption process is generally good, but I hope to see a decrease in price for adopting a child,” said Lunetta. “I understand why there are so many fees and expenses but I think that a lot more children would be adopted if it wasn’t so costly.”

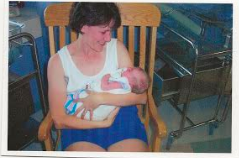

Lunetta in her adoptive mother’s arms. She was adopted from Christiana Hospital days after birth.

Walsh is not reluctant to admit her feelings for the foster care system.

“The foster care system is awful,” she said assertively. Reform was passed after she was adopted, which she believes has created little change.

“Today the foster care system is more of a cash thing than placing children with families and homes to take care of them while they’re separate from their birth parents or while they’re looking for a forever home,” she said. “It’s more people who want to get money and don’t want to work for their money.”

However, according to Delaware’s Child and Family Services Plan 2019 Annual Progress and Services Report, “Seventy-seven percent of foster families adopt children – children can stay with one forever.”

Walsh wishes to see more regulations passed mandating background checks for foster families and observation periods to check for signs of abuse.

“It’s very dangerous for the kids, and most of the time the kids are forgotten,” she said. “I was adopted at five, which isn’t that old, but still, when you’re placed in the foster care system at five, you rarely ever get out. I was one of the lucky ones.”