From Colorado Springs to Wilmington: Mrs. Powers’s Air Force Journey

First Lieutenant Powers speaks on the phone in 1987, three years after graduating from the U.S. Air Force Academy. She was stationed at Fairchild Air Force Base in Washington State at the time.

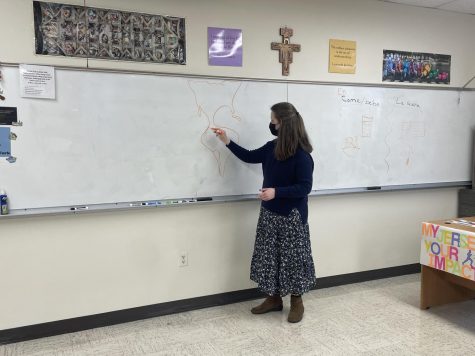

Her students know her as Mrs. Powers, but her former coworkers knew her as Lieutenant Colonel Powers of the United States Air Force. Powers, an English teacher, is one of just 6,369 women to have graduated from the U.S. Air Force Academy. A member of the Class of 1984, Powers served in the military for 20 years filled with unique challenges and rewarding experiences.

The daughter of a Navy man, Powers was born in Norfolk, Virginia, but grew up in New Jersey. A visit to the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, during her junior year of high school sparked her interest in attending a military academy. She said she was impressed by the “beautiful campus” and the midshipmen because “seemed like they knew what they were going to be doing in life.”

“I found out that they got paid to go to school there, they had a guaranteed job for five or six years at least, and I thought, ‘That’s not too bad,’” Powers said. “… I thought it might be kind of cool to be on a ship like my dad had been, and so after that I decided that I would apply.”

The application process for the academies involves earning a nomination from one of the candidate’s Senators or Congressional Representative. Powers said she wrote essays, took a fitness test, and completed interviews to finish her application.

However, her congressman only had a nomination available for the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado, but not the Naval Academy. After completing some research on the school—in an actual library, Powers noted—she decided to accept the Air Force nomination.

“I was so excited,” Powers said. “I really wanted to leave South Jersey. I mean, it was fine for growing up, but I wanted to go out and explore the world.”

While not originally her first choice, Powers said she looked forward to skiing in the Colorado mountains while at the Academy. But before she could hit the slopes, Powers had to endure the intense six-week Basic Cadet Training that culminated in her class’s formal acceptance into the school as fourth-class cadets. During the “shocking” experience, she said that nearly every night, she planned to tell her superiors the next morning that she wanted to leave.

“I did not like the way that we were treated,” Powers said. “I thought we would be treated more like adults and future officers, and I just felt like they kept yelling at us and no matter what we did, we were wrong.”

And Powers was treated differently not just for being a freshman, but also for being a woman. The Class of 1984 was only the Academy’s fifth to include women, and the school allotted them a mere 10 percent of the spots.

Powers said she thought that since the first women had already graduated and all four classes included women, their presence would not be a novelty anymore. However, upon her arrival, she learned that “it still kind of was.”

“There was still some resentment from some of the male officers in particular,” Powers said, “[and from] some of the older young men who were cadets there, especially junior and senior years, because they remembered when there weren’t women there.

“And they somehow thought that bringing women in would lower the standards.”

Even in the overwhelmingly male-dominated environment, Powers succeeded in pursuing her degree and preparing for her career. Powers said the curriculum gave her a “pretty varied background” in subjects she would utilize during and after her time in the military.

“They offered students to concentrate and take some other classes and other areas, and I chose humanities,” she said. “I took Russian history, Russian literature, a Shakespeare class, which shocked me—I didn’t think that would be available there.”

Upon graduation, Powers and her classmates commissioned into the Air Force as second lieutenants, most committing to at least five years on active duty. Powers entered the supply career field partly because her vision disqualified her from flying. Powers was also offered a navigator position, but she opted out because she would “rather be working with people” and simply did not enjoy the tasks.

Even if she had become a navigator, Powers knew she would only be allowed on transport planes, not fighters or bombers. In the 1980s, the Air Force still barred women from flying in combat. This required gender discrimination did not end in the branch until 1993.

“It was kind of shocking because I’d never been told, ‘You’re not good enough,’ or I’ve never been told, ‘No, you can’t do something,’” Powers said.

Although Air Force restrictions limited her job opportunities, serving in the armed forces still offered her the chance to live and work in places across the globe. Powers has lived in Belgium, Germany, and Korea and traveled to Egypt, Israel, Qatar, and other countries on assignment. She said her work in Belgium during the final years of the Cold War was particularly interesting.

“We were there to put in ground-launched cruise missiles that would ultimately be outfitted with nuclear weapons as a deterrent to the U.S.S.R. crossing into Western Europe,” Powers said.

During her career, Powers married and had children, and she was seven months pregnant during not one, but two international moves. She noted that the military had “a pretty good support for families” like hers.

“The childcare center takes babies at six to eight weeks,” Powers said. “They also have families who will care for young children on the base, so I always had a place where the kids could go while I was at work.”

As her children grew older and she climbed the ranks, Powers realized that as a lieutenant colonel, she would be moving even more frequently, possibly every one to two years. With her oldest daughter soon entering high school, she retired from the Air Force after 20 years of service.

“… I really wanted them to have some stability because we had moved around pretty frequently,” Powers said. “And the older they got the harder it was to leave their friends.”

After retirement, Powers and her family settled in Delaware, and she spent time at home to be more involved with her children. When her oldest started driving, Powers “got bored and… wanted something to do,” so she began substitute teaching. She then transitioned to full-time teaching at St. Thomas More for 13 years, moving to Padua after the school closed.

Reflecting on her time in the Air Force, Powers discovered that the military does things “beyond just dropping bombs.” Being an airman gave her the chance serve and see the world simultaneously.

“I always wanted to have a job where I felt like I was serving my community [and] my country,” Powers said. “… I know it’s really kind of idealistic, but I enjoyed the community and the opportunities to travel and see different perspectives and different parts of the world….

“I think it’s a great way of life, and I’m glad I got to experience it.”

Emily Malone is a part of the Multimedia Journalism class at Padua and is editor and chief of Padua 360. She is a Senior at Padua who graduated middle...