Former White Supremacist Speaks About Hate, Inclusion

Christian Picciolini was once the leader of a white supremacist movement. Today he helps hate-filled individuals find a different path.

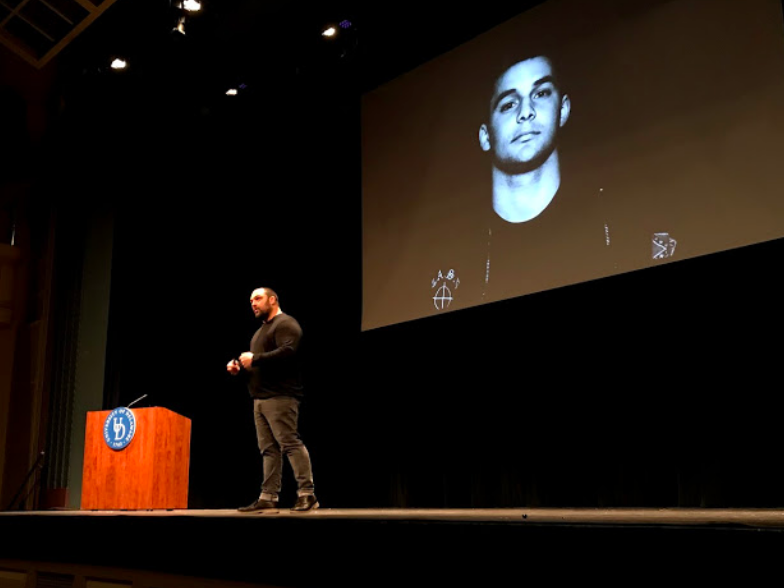

Picciolini shows a picture from his time in the skinhead movement. He has since reconciled with many of those he harmed, and helped many others to leave the movement.

Christian Picciolini grew up in an “Italian bubble” on Chicago’s south side. He had a loving childhood surrounded by aunts, uncles, and grandparents. At 14 he joined a white supremacist movement. He was the leader by 16.

Jenny Lambe, a professor in the University of Delaware’s Communication Department, first conceived of Speech Limits in Public Life: At the Intersection of Free Speech and Hate, around three years ago when she began to recognize an increase in hate speech on social media and college campuses. She planned the conference for over a year and a half, and Christian Picciolini struck her as the perfect fit to open the event.

“I thought he could tell a different story than most academics,” she said. “I wanted somebody that would be interesting and different.”

Picciolini was once a voice for white supremacy, instilling hatred and fear in others. Today he dedicates his life to speaking out against hate and helping disenfranchised individuals find a path away from white supremacy and anger.

When he was 14, Picciolini found himself in an alley, smoking a joint. A skinhead approached him, and he quickly found himself swept into the movement.

“He asked me what my name was. I was always afraid to tell people my name. I was picked on because of my last name, it’s hard to pronounce,” he said. “But when I [told him] he put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Oh, well, that’s a fine Italian name. Your ancestors were great warriors, thinkers, and artists, but there’s somebody out there who wants to take that away.’”

Picciolini was not raised by extremists. But he was searching for what many boys of 14 do—a sense of identity—which he found in that alley.

“I was not there because of the ideology. I clearly didn’t know anything about it,” he said. “I was led there by what I call potholes—those things that appear in our life’s journey that deviate our path. Potholes are trauma, abandonment, like it was for me, mental illness, poverty, even privilege.”

His identity with the movement was always about filling a void, or a pothole.

“While I was a part of this movement, I hurt people, I was violent. I created propaganda to influence other people. I wrote music, racist music. I sold records,” he said. “I took my band to Germany in 1991, and a teenaged me played in front of 4,000 skinheads that had come from all over Europe.”

He was fooled into thinking that he was saving the world. But when he stepped off the stage and saw the violence that followed, he began to see the consequences of his words.

“I knew that I was a part of something that was hurting people,” he said. “But I also know that myself, everybody else that I ever met, that the hatred that we felt was not about anybody else. It was always self-hatred.”

After a marriage, children, and a divorce, Picciolini’s life began to collapse.

“Frankly, I would wake up every morning wishing I hadn’t,” he said. “I still didn’t know who I was. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do with my life. And I really never filled those potholes.”

He managed to secure a job at IBM, and soon found himself facing a black security guard with whom he had gotten in a fistfight at one of his old high schools. He apologized.

“We talked for about a half hour, we hugged, we cried,” he said. “He made me promise that I would go out there and tell my story and try to repair the damage I had caused.”

It was a compassion he didn’t feel he deserved, emphasizing that the burden should not fall upon the victim. But on the other hand, he said, it was the only thing he had ever seen that could break hate.

“What’s happened over the last several years is that recruiters have started to… go to safe zones on the Internet,” he said. “They’ve gone to gaming platforms, they’ve gone to depression forums, they’ve gone to autism forums. They’re banking on the fact that there are people there who feel marginalized in real life.”

Since leaving the movement, Picciolini has helped over 300 people disengage themselves from hate.

“I don’t do that by arguing with them ideologically,” he said. “I don’t shame them, I don’t punch them, because I know that that just pushes them further down whatever hole they’re in… What I do is listen.”

“We need to teach them inclusion. We need to take them out for Indian food, we need to take them out for Japanese food,” he said, explaining that a deeper commitment to inclusion will help to eliminate fear and self-hatred.

Lambe hopes that students took away “some sense of agency” from the talk in order to combat hate speech on campus.

“I hope they’re more aware of when it’s happening online and around them,” she said. “I hope they feel like they can do something.”

Stella White is a senior at Padua Academy. Born in Delaware, with a wonderful British accent, Stella has spent a lot of her life growing up in England....